Since our involvement as invited artists with the Moskonstruct campaign, and later with RKM, where we took care of the communication and graphic design of the EU funded cooperation project, we have found ourselves involved in the issue of preserving the heritage of modernist architecture. Our project and blog have also become a sounding board for campaigns and petitions. This is a quite puzzling matter for us, who have developed our approach to the urban exploring and sometimes colonising intersticial spaces, practicing psycho geographical derives and critical reappropriation of abandoned spaces. In the course of the time, we have beenattracted by the decadence of spaces which represented past social and political organisation forms and by their organic potential as fields of transformation, rather than idealising their architectural embodiment as an heritage to preserve.

Our relation with modern architecture is definitely critical, starting from an initial assumption of its ideology as a planetary-scale failure which provided field for the establishment and continuation of social injustice, domination and segregation. In the course of our wandering into the dilapidated territories of the modern city, our sentiment has definitely shifted, becoming more nuanced and intrigued as if a sort of Stockholm syndrome had taken over us. It is however evident that modernism in architectural and planning terms contains all the elements of the modern society’s contradiction, being at once a revolutionary utopian elán and a reactionary tool of restoration and oppression, expressing both formal beauty to a superhuman extent and ugliness that borders on the sexy. In any case, the legacy of modern architecture has always been approached by ogino:knauss as a fertile territory to metabolise, an open field for the practices of the everyday to reinvent social relations and re-enhance autonomous agency. Therefore, we feel a little uncomfortable when the discourse is restricted to the pure issue of preserving architectural masterpieces.

Our relation with modern architecture is definitely critical, starting from an initial assumption of its ideology as a planetary-scale failure which provided field for the establishment and continuation of social injustice, domination and segregation. In the course of our wandering into the dilapidated territories of the modern city, our sentiment has definitely shifted, becoming more nuanced and intrigued as if a sort of Stockholm syndrome had taken over us. It is however evident that modernism in architectural and planning terms contains all the elements of the modern society’s contradiction, being at once a revolutionary utopian elán and a reactionary tool of restoration and oppression, expressing both formal beauty to a superhuman extent and ugliness that borders on the sexy. In any case, the legacy of modern architecture has always been approached by ogino:knauss as a fertile territory to metabolise, an open field for the practices of the everyday to reinvent social relations and re-enhance autonomous agency. Therefore, we feel a little uncomfortable when the discourse is restricted to the pure issue of preserving architectural masterpieces.

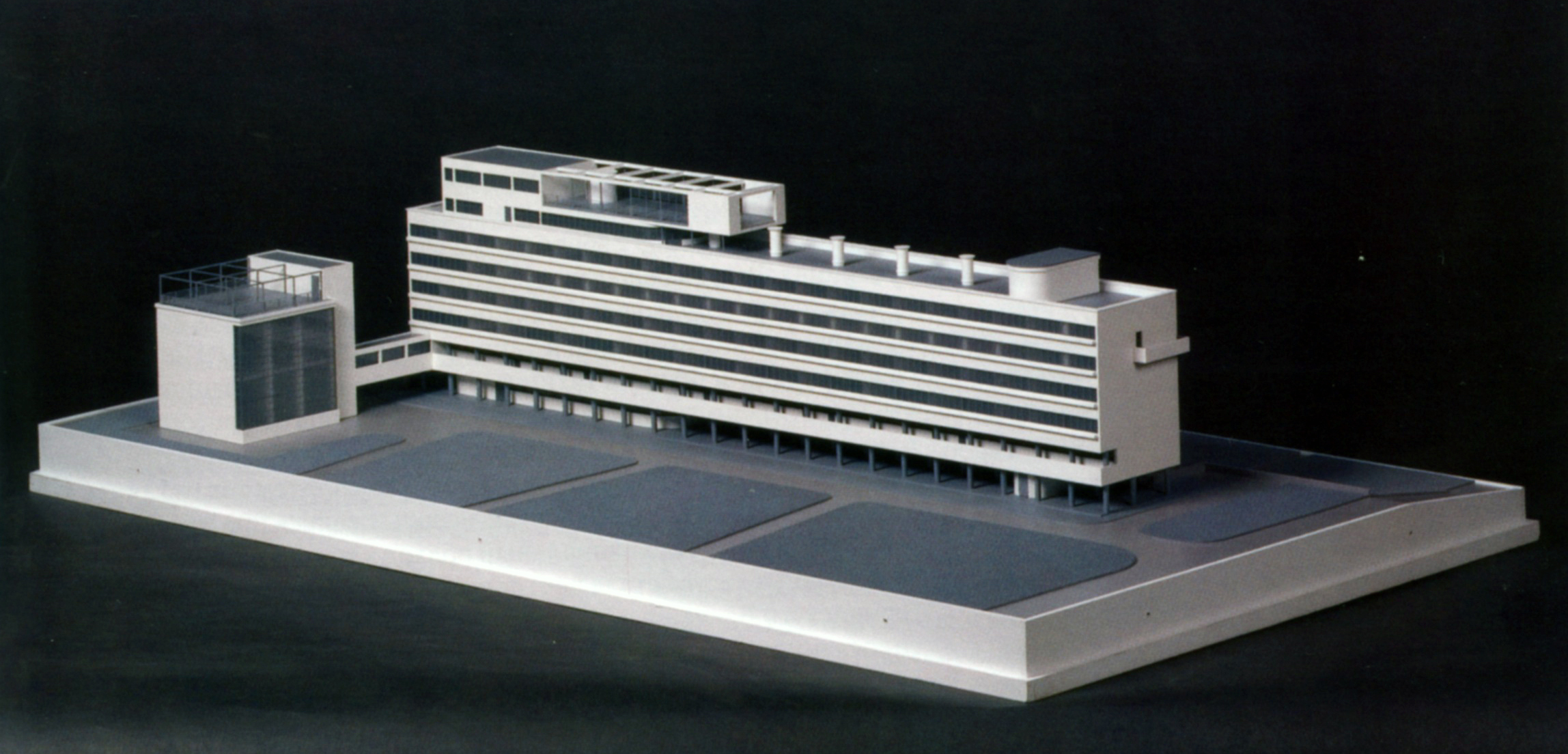

This picture is perfectly reflected in the Narkomfin’s story, which has became the main plot of our film. Here, the interests of those pledging for the restoration of the Narkomfin collided with those of the inhabitants, which clearly understood that they would have never found place in the renovated building. As the developer who bought most of the apartments to redevelop it into a luxury boutique-hotel frankly put it, the inhabitants have no role in Narkomfin’s fate: this is a game between the private company owning the apartments and the public institutions owning the building. Moscomansledie, the municipal agency in charge of preserving cultural heritage, by its part does not seem at all interested in taking care of the survival of the building, as it demonstrated by leaving it dilapidate for decades, neglecting even the proposal of practical intervention advanced by international institutions worrying about the fate of the Constructivist masterpiece. Rather it looks like the Moscow institutions interest lies in clearing away the site from human interferences, if not from the building itself, given the incredibly high value of the land plot with great investment potential in a central position. On the other front, the private company MIAN acquired most of the property with at least a partial interest in its quality as an architectural masterpiece, but obviously subordinated the restoration of the building to its redevelopment as a profitable enterprise. In doing so, it established a cultural foundation, involving scholars committed with heritage preservation and the grandson of Moisei Ginzburg himself in designing the renovation project. Project which on one hand proposes the restoration of the original form of the Narkomfin as designed by Ginzburg, including the piloti loggias filled already in the 1930s with apartments to respond to the dwelling crisis; on the other, transforms it into a luxury hotel totally betraying the communitarian (if not communist…) spirit of the original project. Myopic pragmatism and faithful adherence to formal elements of the architectural style mark the tepid support of preservationist institutions to such a plan. Should therefore have we supported the residents’ position against the plans? Well, certainly our personal approach siding in principle community struggles suggested us to take their side, but in the end, the majority of them revealed to be to there to defend their private property from intruders like homeless squatting empty apartments or artists temporary occupying the former collective rooms for public events, and bargaining to exchange their property for more suitable apartments in an equally valuable urban location. Not that we want to stygmatise their struggle to defend their rights, but in the end, in this story we found that what was totally missed by all parts was the value of the building as the heritage of an age of hope into new social horizons and justice. And how in the end we put it in our film, who does care today of this heritage?