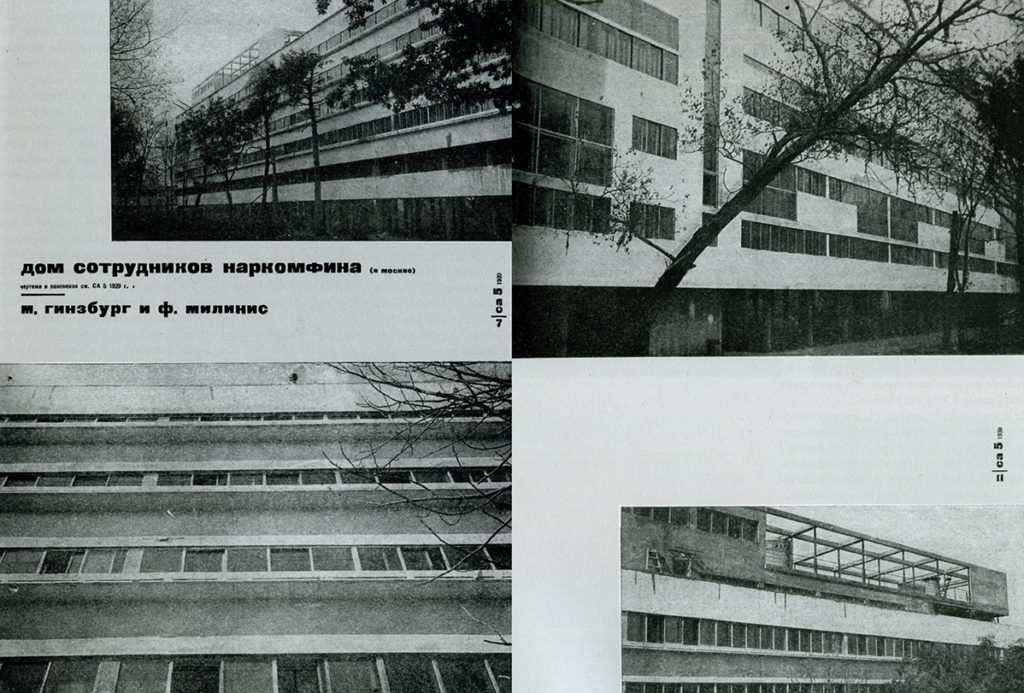

We are honoured to reblog here the essay by Vladimir Paperny originally published in the book O’NFM_6: Narkomfin, edited by Danilo Udovicki-Selb, published by Ernst Wasmuth Verlag Tübingen, 2015, given the kind permission of author, editor and publisher. Apart from being flattered by our film Dom Novogo Byta quoted in it as a source, the piece is probably the most complete and updated account of the conflicted vicissitudes of the constructivist masterpiece designed by Mosej Ginzburg and patronised by Nicolaj Milyutin so far.

Narkomfin Narratives: Dreams and Realities[1]

Vladimir Paperny

Our culture develops by short dashes under fire.

Zinovy Paperny

Cultural Shift

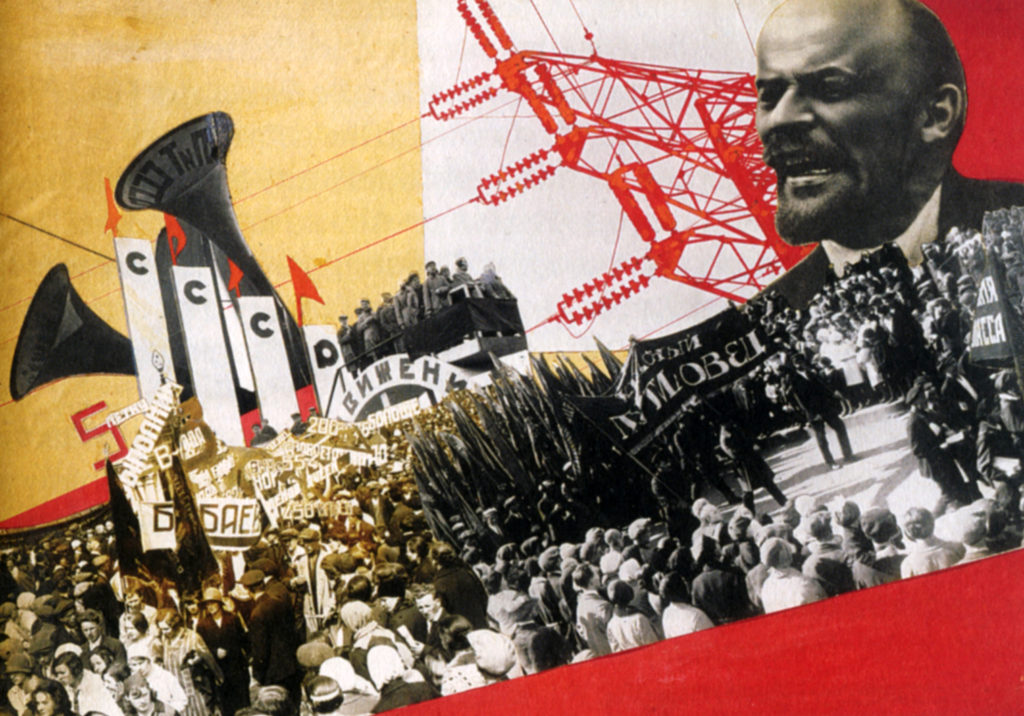

In the late 1920s the development of Soviet culture started going on two separate tracks — and in opposite directions. On the one hand, there was a renewed push to realize some of the Marxist ideals, such as reducing the role of a traditional family, transforming private housekeeping into a social industry, making care and education of the children a public affair, emancipation of women, international workers’ solidarity, and elimination of the distinction between town and country as well as between mental and physical labor. This push was coming from both the remaining idealistically minded government officials and from the avant-garde architects who finally, at the peak of the NEP (New Economic policy introduced by Lenin), had a chance to realize their theories.

On the other hand, there were signs — obvious from today’s perspective but often vague for the participants — of attempts by a small group of people, who were actually running the country, to prepare for war.[2] Their efforts were aimed in exactly the opposite direction, at strengthening of the traditional family[3] in order to increase birthrate and to strengthen the control over the population; sealing the state borders to prevent people from leaving the country,[4] and to curtail contacts with foreigners; strengthening of labor discipline[5] by adopting stiff penalties for minor violations, and by creating labor camps; [6] generating hard currency to finance industrialization, the main sources of which were selling nationalized royal jewelry, masterpieces of art,[7] and grain.

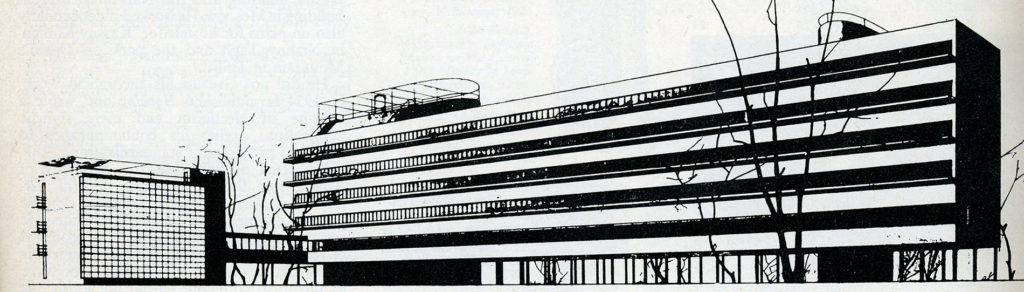

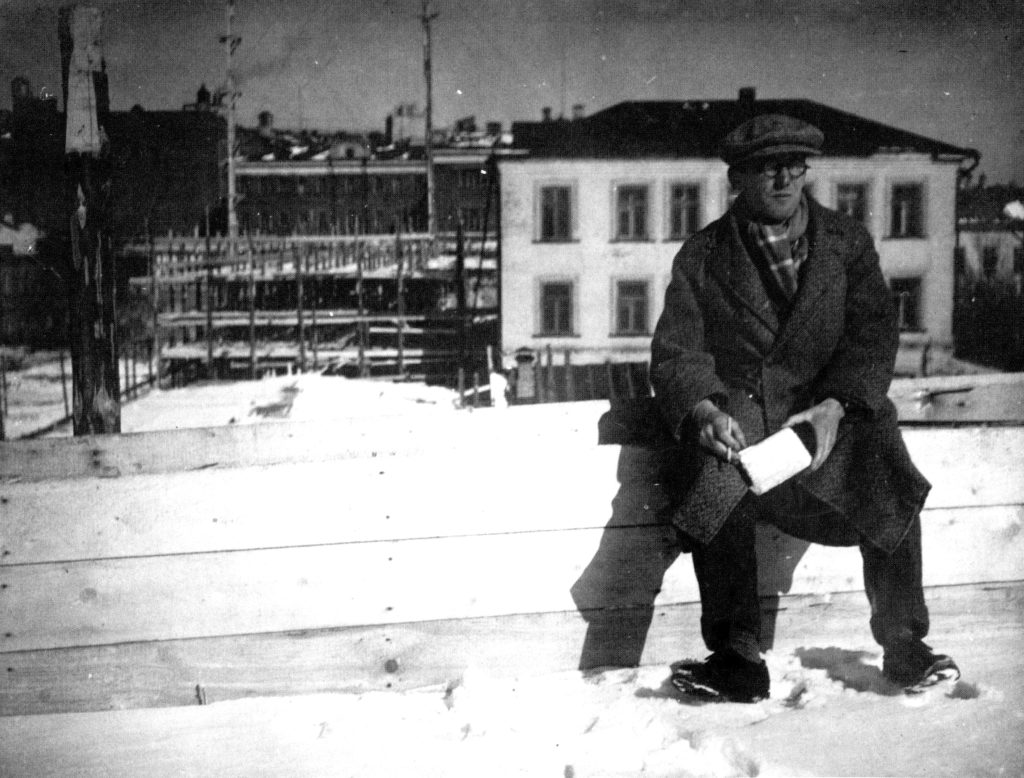

In 1928, when Moisej Ginzburg and Ignatij Milinis were about to start construction of the Narkomfin building, this clash between the two opposing trends was already present. On some level, internationalism, collectivism and Lenin’s NEP were still operating principles. The First Exhibition of Contemporary Architecture organized by Ginzburg’s OSA, with many foreign participants, took place in July-August 1927. In October 1928 Le Corbusier won the commission for the Centrosojuz (Central Union of Consumer Societies) building in Moscow, while the Centrožilsojuz (Central Union of Housing Cooperatives) published guidelines for a typical dom-Kommuna (house-commune), which prohibited “drunks, hooligans and icons.”[8] These guidelines were ambiguous — they endorsed the collectivist lifestyle and, at the same time, enforced strict discipline.

In 1928, measures were still taken to “maximize use of private capital in housing construction,”[9]but on the other hand, the 15th Congress of VKP(b) explicitly demanded “to reduce and eliminate capitalist elements from the economy.”[10] In 1928, contacts with foreigners were sharply curtailed. This could be seen, for example, is the abolition of the Committee for organizing exhibitions of foreign technology.[11] A little later, Le Corbusier’s letters and books sent to his Soviet friends started to be returned to sender.[12]

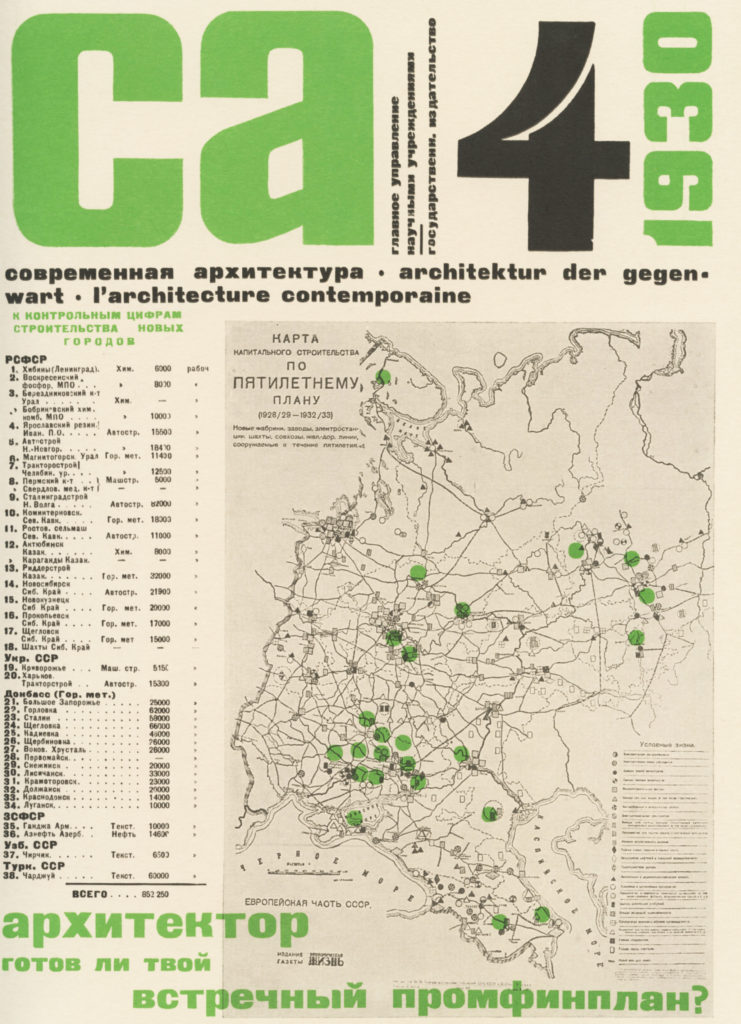

The 15th Congress of VKP(b), which took place in December 1927 (later called the Collectivization Congress), marked an important watershed in Soviet history. A resolution was adopted to develop the first 5-year plan (perhaps, influencing nine years later the Nazi 4-year plan). Leon Trotsky and Grigory Zinoviev were expelled from the party following their anti-Stalin demonstrations in Moscow and Leningrad on November 7. At the Congress, for the first time in the fight with the opposition, “incriminating evidence” of arrested opposition leaders, obtained by the secret police, was used. “One of the opposition leaders arrested by GPU,” said delegate Leonov, “confessed that he had discussed the preparation of terrorist acts.”[13]

Various approaches to collectivization of agriculture were debated throughout the 1920s but it was only on December 27, 1929, that Stalin came up with the formula “liquidation of the kulaks as a class on the basis of total collectivization.”[14] The word “collectivization” bears some overtones of the previous epoch — of spontaneously emerging house-communes of the early 1920s, of Konstantin Melnikov’s collective bedrooms, and even of the Narkomfin communal house itself. But the reality behind the word was quite different. In fact this the “liquidation of the kulaks as a class meant effectively the physical elimination of a certain class of the population. The consequence of forced collectivization of 1929-1941 more than 2 million peasants were deported, 6 million died from starvation, of which hundreds of thousands in exile. Despite of unprecedented hunger, a large part of expropriated grain was sold abroad to finance industrialization. The large cities were surrounded by armed soldiers to prevent dying peasants from entering, yet 1929-1941 in Russia was the period of the highest rate of urbanization in history.[15]

When one reads architectural journals of that period, Sovremennaja Arhitektura (Contemporary Architecture, 1926-1930) or Sovetskaja Arhitektura (Soviet Architecture, 1931-1934), it’s hard to believe that architects of the Russian Avant-Garde lived in the same country as the rest of the population. Events, which some historians called “Stalin’s revolution” or “Stalin’s counter-revolution” and which as easily could be called “the Second Russian Civil War,” left no traces on the pages of these magazines. Very talented architects continued to present their brilliant ideas, discuss technical innovation and ways of eliminating the distinction between town and country — as if they lived in an ivory tower, oblivious to the horrors outside.

But soon the bombs started falling closer. In 1935, Mihail Ohitovič, Ginzburg’s close associate, was arrested and eventually executed. In 1934, Aleksandr Smirnov, to whom Nikolaj Miljutin (Ginzburg’s client and collaborator) had dedicated his book Socgorod, was expelled from the party and later executed. In 1936, another Ginzburg’s close collaborator, Solomon Lisagor, disappeared in a similar fashion.

“What was Moisej Ginzburg’s relationship with Marxist ideology,” I asked his grandson Aleksej, also an architect.

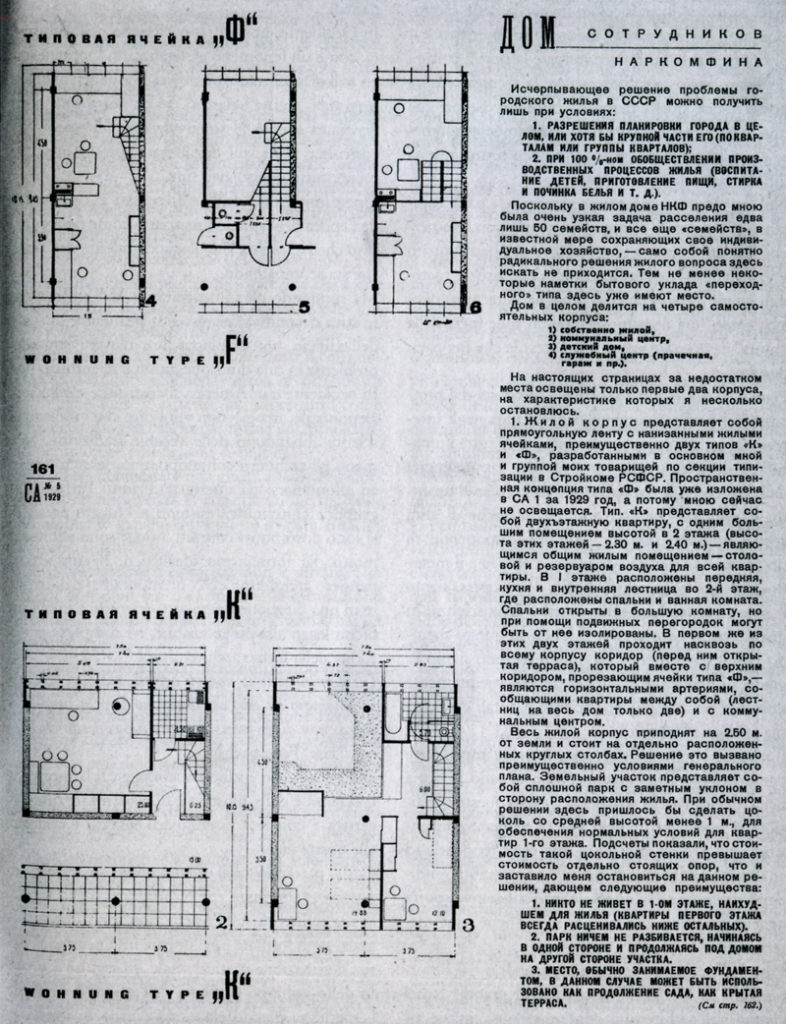

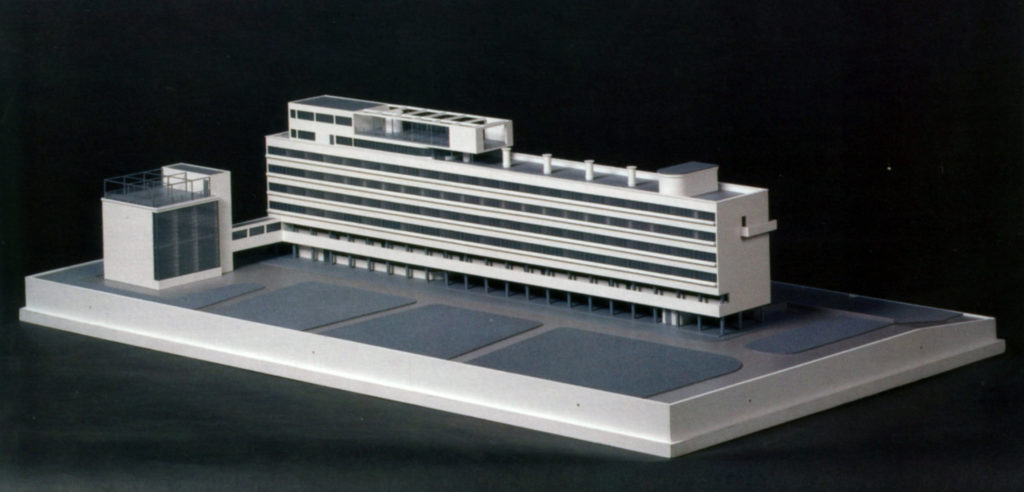

“His book ‘Style and Epoch’,” Aleksej replied, “was not about some bright communist future. It was about the modern world and the new challenges, which needed to be answered. There is a big difference between a house-commune and a communal house like Narkomfin. Ginzburg proposed a way of life, which now seems natural, because we all live like that. Ginzburg added large public spaces to small apartments, plus all the necessary functions — a kindergarten, a gym, a café, a laundry room. He managed to formulate and answer a question: what should be a human dwelling in the modern era.”

“So,” I asked, “all his Marxist phraseology was just mimicry, desperate attempts to survive?”

“Your guess is as good as mine,” he answered.[16]

I believe that an astute observer and a logical thinker, as he was, Moisej Ginzburg understood perfectly well what was going on in the country. At some point, he made a conscious decision to concentrate on strictly professional tasks in order to stay alive, and he succeeded. But even in the professional sphere, he had to make sacrifices. His sanatorium in Kislovodsk or a proposal for a young pioneer camp Artek show a noticeable retreat from his early ideas. Luckily, the Narkomfin building was finished before a stiff control over the USSR construction industry was established. The transitional period between two dramatically different historical and cultural periods made the “transitional type” of a building possible. Moisej Ginzburg was able to leave a lasting legacy, where his theoretical and practical insights came together in a single architectural complex. After this unique building was completed, its fate was beyond Ginzburg’s control.

The Narkomfin’s Dwellers

The building was intended for the employees of the People’s Commissariat for Finances. It was considered a prestigious place to live. “The house was for the elite,” says Aleksej Ginzburg, “although today the word ‘elite’ makes everybody cringe. This included, besides the Ministry’s employees, writers, artists, Ginzburg himself and other architects.”[17]

As Miljutin’s daughter Ekaterina remembers, “First there were people working for the Ministry[18]and then people working with the Ministry. This was the case among others of Rabinovič, a sergeant with the Red Army, or Nikolaj Semaško,[19] a physician. A lot of bohemians were happy to move there. Aleksandr Dejneka[20] was on the second floor. His wife Šima, a very fancy lady, had a wonderful convertible car, like those we see today. It was just incredible.”[21]

A possible story about the origin of the penthouse Miljutin built on the Narkomfin, as Ginzburg grandson reports, is that Ginzburg and Milinis wanted to come up with the most modern ventilation system, but at the end, there was not enough money to buy the equipment. Since the ventilation room on the roof had already been built, Miljutin decided to convert it into an apartment for his family, and actually constructed a ‘type K’ cell there. Ginzburg and Miljutin quarreled terribly about it because the drawings had been already published in many magazines. They later reconciled.”[22]

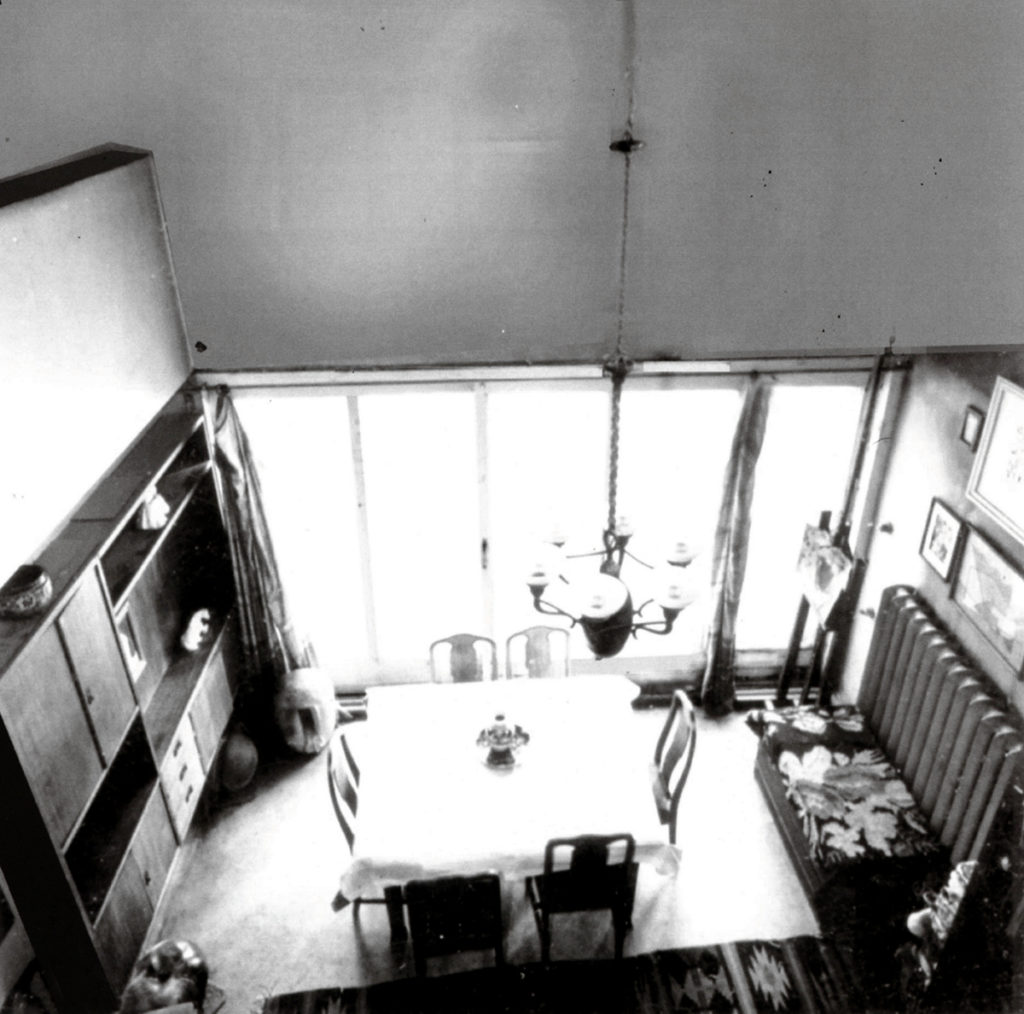

For his own family Moisej Ginzburg selected the most spacious “type K” apartment with two levels and five rooms. There were eight apartments like this in the building, two on the second floor — Ginzburg’s and Dejneka’s. Within the whole social strategy of the project, these apartments implied the most traditional way of life.

Still, certain democratic principles were maintained. Miljutina continues: “Actually we did not have any [social] barriers. Cleaning ladies of the Narkomfin had their apartments here, as did ministers, and all the children played together, we did not make any difference. When we prepared for exams, everybody was in our apartment, and it was 20, 30 kids maybe, studying for the exams, there was no sense of privacy like we have it here [in the US]. It was private in a sense, but at the same time we lived… collectively!”[23]

By the time Miljutin had his penthouse, his political standing became shaky. “He was in conflict with Stalin,” says Ekaterina Miljutina, “he left Stalin’s office slamming the door but, strangely enough, he was never arrested. Most often people who were very friendly to Stalin but spoke badly behind his back, they were arrested, but he was never arrested, though he was very, very nervous and maybe that caused some of his illness.”[24] Elsewhere, she elaborated: “He slept with a gun under his pillow, saying ‘they are not going to get me alive’.” [25]

Ekaterina Miljutina was born in 1936. Her rather idyllic memories of her childhood do not include the period between 1937 and 1938 when most of the residents of the building suddenly disappeared. The Memorial society[26] has a list of 19 residents executed as people’s enemies (see Appendix) who had lived in the Narkomfin. Among them:

- 17 members of VKP(b);

- 3 People’s Commissars;

- 2 deputy People’s Commissars;

- 9 people with the title “head,” “director,” “chairman,’ or “manager.”

The Memorial Society does not have a list of residents who were arrested but not executed and sent to labor camps instead. It is safe to assume that there were at least as many. In short, more than a half of the residents of the communal house disappeared between 1937 and 1938. A large number of them ended up in the barracks of labor camps, experiencing the terror of total “collectivization.”

During and after World War II, the empty space under the building was enclosed and turned into ground floor apartments, thus destroying the house’s original character. The same thing happened with Le Corbusier’s Centrosojuz building in Moscow — the look of a building floating in air contradicted the traditional vision of a building “growing from the ground.” Le Corbusier’s Centrosojuz building in Moscow was restored to its original shape in the 1980s. The Narkomfin never was.

Attempts at Restoring the Building

The very first attempt to save the building, which had never undergone any substantial repairs, was made in the mid-1980s by Moisej Ginzburg’s son Vladimir and grandson Aleksej — without the help of any client, sponsor or government. Vladimir’s fate was rather tragic. He became an orphan at the age of 16 and decided to become an architect as a tribute to his father. Vladimir Ginzburg and his friend Kogan entered the Moscow Architectural Institute (MAI)[27] in 1952. That was the time of the infamous “killer-doctors” trial. Kogan’s father was one of the doctors arrested in connection with the “Zionist conspiracy.”[28] Kogan junior was expelled from MAI as a son of a people’s enemy. Vladimir Ginzburg was also expelled for not reporting Kogan to the authorities. After Stalin’s death, as all doctors were released and acquitted, Kogan-son was readmitted to MAI, his guilt no longer existing. Ginzburg-son was not. His guilt was still considered valid: he did notreport Kogan. Instead, Vladimir graduated as architect from the Institute of Land Management.

Vladimir Ginzburg disappeared in 1997, under mysterious circumstances. It was suspected that he had been kidnapped and killed by members of a real estate mafia because of his opposition to some of their plans, possibly related to the Narkomfin. The body was never found. There was some tragic irony in the fact that Moisej Ginzburg had managed to survive “gangster socialism” of the 1930s, while for his son “gangster capitalism” of the 1990s turned out to be deadly.

n the second half the 1990s various commercial organizations showed interest in restoring the building. The majority of them had no appreciation for the building’s architectural value. They regarded it merely as a piece of real estate or even a piece of land for new construction. “In such cases,” wrote Aleksej Ginzburg in 2006, “my father tried to explain that the only option here was restoration. He used his moral authority to prevent changing the building’s layout and structure. In 1995, we found what seemed to be an ideal solution: my father began negotiations with an American company, one of whose presidents was himself a professional architect.”[29]

This project, like many others before and after, failed. “The American company,” continued Aleksei, “in spite of its experience in working with real estate in Moscow, suddenly got bogged down in a bureaucratic tangle with Moscow’s Land Committee. Finding themselves up against strong resistance, they abandoned the project after several months of trying.”[30]

Around 2006, the developer Aleksandr Senatorov, the owner of a real estate behemoth MIAN,[31]an “oligarch” and a yoga and martial arts aficionado, became interested in the building. “There were rumors,” says Lorenzo Tripodi in his documentary Dom Novogo Byta, “that a developer decided to invest in the Narkomfin as a pledge of love, his girlfriend asked for, that is, to save the Constructivist masterpiece in exchange for a trip to the altar.”[32]

Aleksandr Evangeli, an art critic and professor at the Rodchenko School, [33] currently lives in the apartment No. 39 of the Narkomfin, the same apartment where Deputy People’s Commissar Vasilij Hronin used to live until he was arrested and executed in 1937 (see Appendix) . He put the Senatorov story in historical context. Says Evangeli

In the middle of the 2000s, “Russian art and Russian businesses were on a rise. The ‘oligarchs’ found it useful to equip themselves with girlfriends, who were able to solve the problems of laundering fast money, the dirty initial capital. A perfect tool for that was art. First galleries, then art foundations began to sprout everywhere. Senatorov’s girlfriend, and later wife, Alexandrina Markvo, was not interested in galleries and foundations — they already were becoming commonplace. Instead, she was given these outstanding ruins as a toy. The idea of a boutique hotel emerged. Unfortunately, we know too well what building a hotel in Moscow means, just look at the hotel Moskva.[34]

Evangeli refers to the system, which initially developed under the former mayor of Moscow Jurij Lužkov, and did not seem to change much under the new mayor Sergey Sobyanin. Architectural critic Grigorij Revzin described this system this way: “If you look at who owns the buildings, for example, the hotel ‘Moscow,’ you will see that the owners are joint stock companies, with names like ‘Corporation Hotel Moscow,’ for example, where 51 percent of stock belongs to the Moscow government, or some businessmen close to Jurij Lužkov.”[35] Obviously, any transformation of the Narkomfin building into a business asset of the Moscow government would automatically preclude it from being on the list of the UNESCO cultural heritage sites.

Senatorov’s first choice was Pavel Andreev, the architect who had been criticized for participating in projects that resulted in destruction of monuments and demolition of historic buildings in Moscow.[36] When activists of the architectural preservation movement learned about Andreev’s involvement in the Narkomfin building, they panicked. Fortunately, Senatorov decided to rely on experts. The first brainstorming sessions were attended by Bart Goldhoorn and Elena Gonsales (Project Russia magazine), as well as Clementine Cecil and Marina Hrustaleva (MAPS[37]). As a result of these sessions, the Senators created the “Narkomfin Foundation” to explore the building and to interact with experts. He finally selected Aleksej Ginzburg as the restoration architect.

“My attitude towards the project went through several stages,” says Alexandr Senatorov. “Our understanding of financial options changed significantly over time — in terms of what we wanted out of this project and what kind of reuse was possible. In the early stages, we thought of converting it into a boutique hotel. Before the crisis, there was a lot of money, and you could work with the most expensive materials. We hoped that some crazy investor would buy it.”[38]

At that stage, selling individual apartments seemed unacceptable. The Senatorov-Ginzburg design proposal of 2008 was very specific: “It is important that the exploitation of the house be designed and implemented as a single system, thus prohibiting commercial sale of apartments. This becomes possible with the creation of an art hotel.”[39]

After the financial crisis, the idea of a boutique hotel did not seem attractive anymore. “Yield is determined by the rental market, amounting to 3-4%,” according to Senatorov’s latest claim. ”You cannot borrow money in Russia at this rate, so it becomes an unprofitable operation. Selling condos gives a radically different return.”[40]

Looking for ways of converting apartments into condominiums, Senatorov decided to try something radical. He asked himself, what would it take him to want to live there? Everything about the building seemed perfect. Manageable apartments, great location. For the yoga and martial arts enthusiast there was only one thing missing: sport.

Therefore, Senatorov’s latest project involves building a swimming pool in the narrow strip between the building and the fence of the expanded territory of the American Embassy.[41] The ground there is sloped towards the fence. In the proposal, the sloping lawn abruptly goes up, becoming the roof of the pool. In essence, Senatorov wants to create something similar to the grass-roofed Hypar Pavilion in the Lincoln Center in New York, although he admits that he has not seen it.

Senatorov’s chances for success seem to be low. First, the Narkomfin building has the official status of an “architectural monument,”[42] and to get permission for digging next to it, even from the notoriously corrupt Moscow bureaucracy, is close to impossible (not to mention any ethical considerations). Second, building anything within a few meters from the Embassy may be problematic for both the Russian and the American security organizations. Senatorov is, nevertheless, optimistic: “Maybe the Americans would buy a few apartments, for them it is an

ideal place — small apartments, hotel service, and could not be closer to work. We’ll talk to McFaul.”[43]

There is a dim ray of hope in the fact that “saving masterpieces of the Russian Avant-Garde architecture” appears more and more often on agendas not only of grass-root organizations like MAPS and Arhnadzor[44] but of the government structures, such as the Moscow City Hall and the Moscow Urban Forum.

Current Residents and Lifestyles

Current living conditions in the building violate every imaginable building code and sanitary norm. “Narkomfin is being exploited like a natural resource,” says one resident. “Whoever owns the apartments is just collecting rent, but doing nothing for the building. No repairs, nothing.”[45] The rents in the Narkomfin are steadily rising. Currently, most of the residents pay 40,000 rubles a month ($1,257) for a rundown place.

In the late 1980s, Soviet housing authorities found the Narkomfin house “unsafe” and started offering residents comparable apartments elsewhere. Many accepted and moved out. Some kept bargaining for a better deal but negotiations collapsed with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Since 1998, residents could legally privatize their apartments. Some Narkomfin residents did, some decided against it. By 2006, when Senatorov became interested in the building, only about 12 apartments were occupied, some of them privatized. The rest were abandoned, all pipes and cables literally cut off by the authorities to prevent squatting. Nevertheless, the remaining residents used some of the abandoned apartments as storage, with illegally installed locks.

In 2006, Senatorov started acquiring apartments, negotiating with owners of the privatized ones, and with the City Hall about the abandoned ones, eventually purchasing 30 out of 46 lodgings. In 2010, Nikolaj Palažčenko, an art dealer and curator of the art center Vinzavod[46] approached Senatorov, saying: “you have empty apartments and I have talented artists with no place to work.” With the help of Senatorov’s management company, Palažčenko started renting out vacant apartments to his creative friends — artists, designers, and photographers.

On the “creative” side, there are people like Donatas Grudovič, actor, producer, and a performance artist. He used to live in former Dejneka’s apartment (No. 18) but recently was kicked out by some residents, with the help of the police, for his noisy performances. He described his living condition with sneering humor: “Every morning I have to shit in a plastic bag and throw it over the fence to the US embassy. I already gave all my booze to the plumber…but to no avail.” But this, to him, is a fair price for living in a Constructivist masterpiece. He loves Futurism and would want to recreate some of the communal ideals of the 1920s: “I wish we could have a real commune here. So that everyone could live here, work on one common project and wear some kind of uniform.”[47] He is fascinated with the ideas and symbols of the early Soviet past. Before the opening of one of his performances, ‘The Morning of the Useful Time,’ he requested that all involved swear that they’ll willingly embrace whatever might happen, even if they didn’t like it; that they’ll carry on and will not leave the group. This is where his fascination with the Soviet past borders on parody. Still, he seems quite serious. “Repeat after me,” he goes on, “I renounce my name and solemnly swear to be loyal to the common purpose. I renounce all names and titles.”[48]

Today, residents comprise actually a very diverse group of people. Some stay simply because they are stuck, having missed out on both the offers from the Soviet authorities in the 1980s and privatization opportunities of the perestrojka era. In general they don’t like the building and don’t care about the avant-garde. One of them, Viktor Suvorov, grumbles in a documentary: “They call it ‘Constructivism’ — bloody Jewish Constructivism.”[49] Inevitably, there is an ongoing conflict between these people and the “creative” group initially recruited by Palažčenko.

Another resident, Aleksandr Evangeli tries to explain what makes him stay in the building: “Constructivist architecture was a utopian humanitarian project, designed to improve consciousness through architecture. This ‘orthopedic’ impulse existed in this architecture from the very beginning, and it was quite repressive. As somebody who lived here for three years, I understand that this architecture is incompatible with certain habits, especially some of the late-Soviet habits, such as hoarding stuff for example. The building has no windowsills. After the revolution through the late 1920s, a windowsill was a symbol of middle-class comfort. There was always a samovar sitting on it and potted plants, usually geraniums. When I moved here, I found several generations fighting this oppressive space. People built sills; all this open constructivist space was boarded up creating cozy little rooms. People built second and third floors, mezzanines, etc. There was nothing left from the original space flooded with light. Even the top row of windows was usually boarded up. What amazed me was the amount of absurdity. These windows are easily manipulated, leaving gaps for air. However, people who lived here, would cut small fortočki (glass vents) into the big window panes. These vents obviously were more difficult to control, but the tradition required to have a small frame within a large one. I have no explanation,” he concludes, “other than it’s the architecture and the desire to make my space… accurate.”

To clarify his point, Aleksandr turns on his computer to show a 20-minute film “Farewell to Fireplace” shot in his apartment by his students from the Rodchenko school. The film has a certain similarity with Grudovič’s “The Morning of the Useful Time.” Both play with the themes of the 1920s — collectivism, feminism and the equality of men and women.

“Farewell to Fireplace” is a silent film, accompanied by atonal piano improvisations. It imitates Constructivist graphics and montage, but is shot in color and high definition. The plot echoes Vladimir Mayakovsky’s play of 1929 “The Bedbug,” Mayakovsky is even listed as the screenwriter: A revolutionary young man dies and is revived in the utopian collectivist future, where all contradictions are resolved. Here too we find a fascination with the Soviet past bordering on parody.

Apparently, what Aleksandr Evangeli is trying to tell us by showing this film is that Ginzburg’s architecture carries a certain aura. People who find themselves in this architecture are forced to think and act in a certain way, which points out — and in that sense only — to the ‘repressive’ character of the architecture.

Almost every resident of the building I talked to was ready to admit that the building possessed a magical ability to influence creativity. Anton and Polina, who now live in the Deineka apartment, formed a clothing company IMAGO, and their unisex uniforms have some similarities with the works of Ljubov Popova and Varvara Stepanova of the 1920s.

Artist and stage designer Vitalij Burikin first walked into the building in 2011. To him the space looked like a set for a horror film. He immediately wanted to live and work there. “Crazy?” asked the doorman. “Yes!” replied Vitalij cheerfully. He finds many “different energies” here. “You can meditate here. The spirit of creativity always lived here and always will, even if everybody’s gone.”[50]

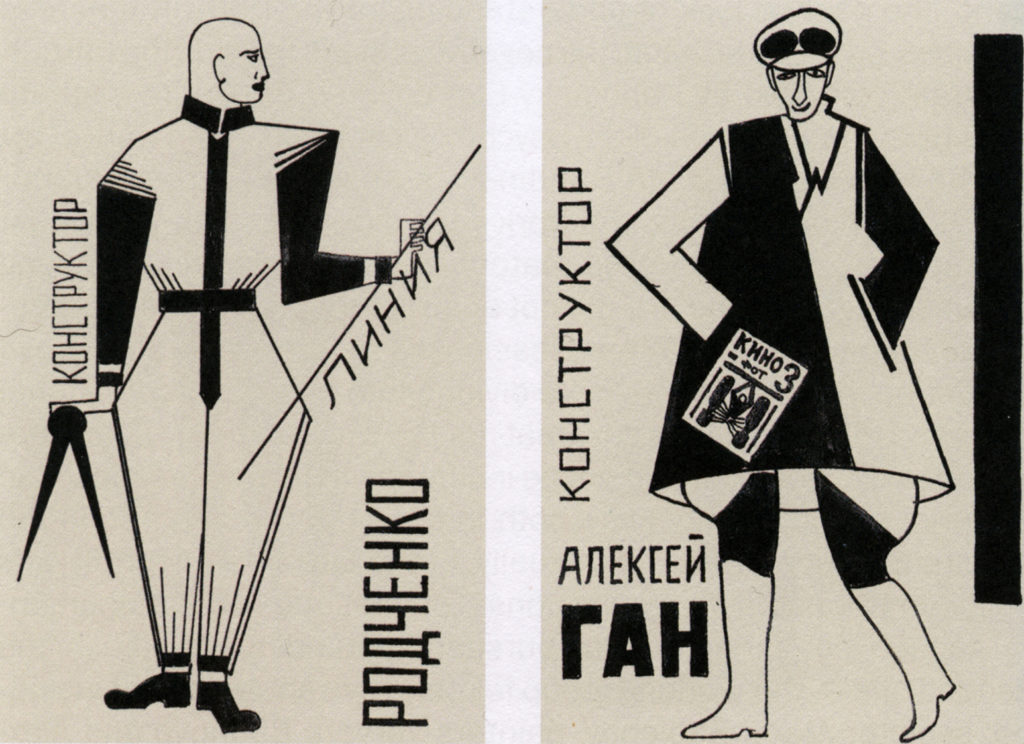

When “oligarch” Aleksandr Senatorov does a handstand on the Narkomfin roof, he looks like one of the characters in Rodchenko famous photographs. At times he wonders: “How did I get into this mess?” But he is hooked on and is not likely to abandon the project, even if he looses money on it, which is almost granted.

In short, this amazing crumbling structure is still affirming the power of creative thinking over unfair, cruel and at times violent circumstances.

Appendix

Residents of The Narkofin building executed between 1937 and 1940.

Source: the Memorial society: http://mos.memo.ru/shot-39.htm#s6Apt. 8. Gurovič, Eduard Jakovlevič, b. 1896, a member of the CPSU, the head of the central administration of the Eastern River Transport of the USSR People’s Commissariat of Water Transport. Executed 08.01.1938.

Apt. 12. Kopylov, Nikolaj Vasil’evič, born. 1889, member of the CPSU, the head of the trust “Orgenergo” of Commissariat of Heavy Industry. Executed 20.06.1938.

Apt. 13. Kriučkov, Pëtr Petrovič, b. 1889, director of the Museum of Maxim Gorky. Executed 15.03.1938.

Apt. 13. Kriučkova, Elizaveta Zahar’evna, b. 1902. executive secretary of the magazine “The collective farmer.” Executed 17.09.1938.

Apt. 26. Polujan, Ian Vasil’evič., b. 1891, member of the CPSU, the head Main Energy Department of the RSFSR People’s Commissariat of Public Utilities. Executed 8.10.1937.

Apt. 29. Buharcev, Dmitrij Pavlovič, b. 1898 member of the CPSU, PhD, a correspondent of the newspaper “Izvestija” in Germany. Executed 3.06.1937.

Apt. 39. Hronin, Vasilij Nikiforovič, b. 1889, member of the CPSU, Deputy People’s Commissar of Internal Trade of the RSFSR. Executed 26.11.1937.

Apt. 41. Gurevič, Moisej Grigor’evič, b. 1891, member of the CPSU, Deputy. People’s Commissar of Health of the RSFSR. Executed 26.10.1937.

Apt. 42. Sokolov, Nikolaj Konstantinovič, b. 1896, member of the CPSU, Chairman of the Board of the State Bank of the USSR. Executed 30.07.1941.

Apt. 42a. Ivanov, Boris Aleksandrovič, b. 1893, member of the CPSU, Head of the Secretariat of the President of the CPC of the RSFSR. Executed 15.03.1938.

Apt. 43. Lebed’, Dmitrij Zaharovič., b. 1893, member of the CPSU, Deputy chairman of People’s Commissars of the RSFSR, a member of the Central Committee of the CPSU. Executed 30.10.1937.

Apt. 44. Strievskij, Konstantin Konstantinovič, b. 1885, member of the CPSU, chairman of the Central Committee of the Union of Workers of heavy machinery. Executed 21.04.1938.

Apt. 45. Sulimov, Danila (Daniil) Egorovič, b.1890, member of the CPSU, chairman of the CPC of the RSFSR. Executed 27.11.1937.

Apt. 46. Krylenko, Nikolaj Vasil’evič, b. 1885, member of the CPSU, the People’s Commissar of Justice of the USSR. Executed 29.07.1938.

Apt. 47. Karp Sergej Benediktovič, b. 1892, member of the CPSU, the chairman of the State Planning Committee of the RSFSR. Executed 30.10.1937.

Apt. 49. Antonov-Ovseenko, Vladimir Aleksandrovič, b. 1883, member of the CPSU, People’s Commissar of Justice of the Russian Federation. Executed 10.02.1938.

Apt. 49. Antonova-Ovseenko, Sofja Ivanovna, b. 1898, housewife. Executed 08.02.1938.

Apt. 50. Nikolaj Lisicyn, b. 1891, member of the CPSU, the People’s Commissar of Agriculture of the RSFSR. Executed 22.08.1938.

Apt. 51. Gerasimov, Ivan Semenovič., b. 1894, member of the CPSU, managing director of SHK RSFSR. Executed 26.10.1937.