The terrain of this modern development, most dramatically beheld from the position of the ancient Belgrade fortress, served for centuries as a no-man’s-land between the borders of the two empires, the Ottoman and the Austrian/Austro- Hungarian. Devoid of any urban structure, it fulfilled the function of a cordon sanitaire, observed and controlled as no-connection- zone between the Orient, where Belgrade, as it were, marked its end point, and the Occident, of which Zemun was the first, even if modest and marginal, port of call. (Liljana Blagojevic)

(…) the initial notion of New Belgrade reflected the non-national character of the Yugoslav society and the political construct of peoples democracy. In that sense, we would propose that the founding of this new city not only demonstrated the concept of centralization but, more importantly, the ambition of the new state for New Belgrade to take precedence over historical constellation of cities, and to became the capital of central state power belonging to no city, i.e., the capital of no-city’s-land. (Lilijana Blagojevic)

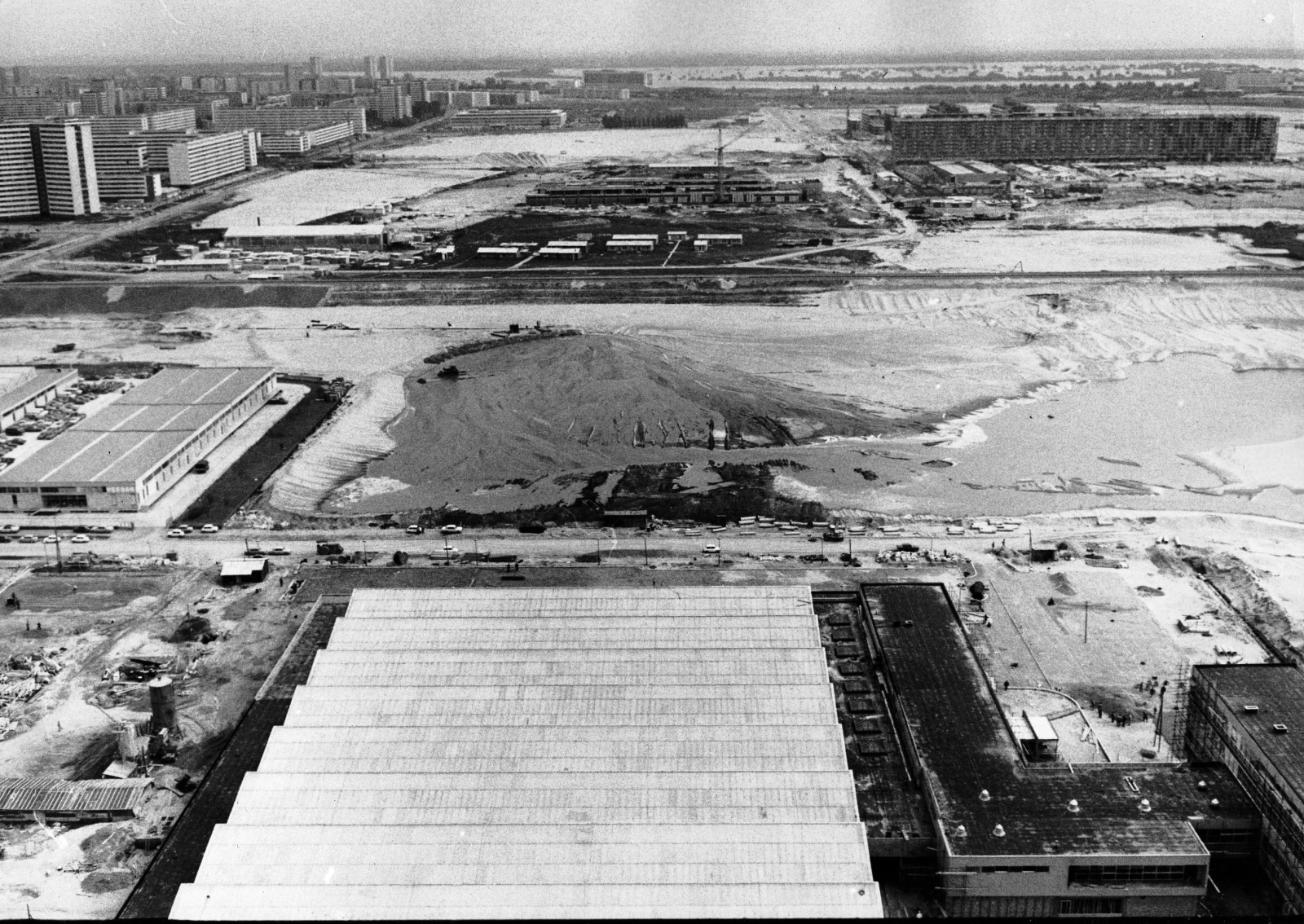

New Belgrade is one of the few modern settlements realizing the dream of the tabula rasa, an entire new city built from scratch, without dealing with any heritage from previous spatial configurations and architectural styles. Novi Belgrade rose up at foothill of the old city of Belgrade on a reclaimed swampland, historically the no-man’s land between the Austro-Hungarian and the Ottoman Empire. The project was launched by Tito in 1948 to create the administrative capital of the Yugoslavian federation. Inasmuch, Novi Beograd does not represent simply the dream of a new city, but also that of a new multiethnic national identity. Today it is a quite populated district of the Serbian capital, and differently from many modernist experiments, it is considered successful in becoming an integrated part of the metropolitan area.