Recently we did a survey in the area of Hellersdorf along the last stations of the S-Bahn line 5. One of the most recent big development areas of former East Berlin, one of the last still adopting the prefabricated, high rise building, typical dormitory city approach. A neighbourhood already under observation for the RCP project. This time we had a particular focus on the names given to the localities and streets, inspired by the exercise in urban reconnaissance City of Names. “Naming spaces create places”…

Who gives a name to a place? Why? What process influences place-naming? Which memories are inscribed in toponyms, which removal and manipulations are disguised in them? Such questions are the starting point for a reconnaissance of Hellersdorf’s hermetic identity…

The exploration takes the cue from the station of Neue Grottkauer Straße. named after a village in Silesia, Grodków, few kilometres south of Wroclaw, that used to be Germany until 1945. The name of the station may soon disappear. Places, toponyms, signs are constantly erased in face of new urban development. So might be silent stories, conflicts and struggles to which they are connected. Recently, part of the signage identifying the station has been removed. We discovered that the renaming of the station as “Gärten der Welt” is expected, and BVG was suggested to change the signs, but the process has been interrupted due to bureaucratic issues. The shift towards a new name is evidently connected with the relevance in terms of urban development that will be given to the place by the incoming IGA 2017 exhibition planned in the green area siding the station, which will become the gate to the International Garden Exhibition. The station, as a matter of fact, is planned to be connected through a ropeway with the entrance of the exhibition, an infrastructure built and funded by an international private investor. Here, even in the deepest periphery of the city, we unexpectedly find the prodromes of a festivalization process at work: the spectacular machine building and promoting big events as essential milestones to condense investment and trigger urban development.

After the crossroad with Eric Kästner strasse, dedicated to the german writer famous especially for his children book Emil and the Detectives , we proceed to the Jelena Šantić friedenspark, a park created in the 1990s and planned as part of a green axes supposed to connect Ahrensfelde with Kopenick. The park is named after a Serbian classical dancer and peace activist who is told to have suggested the realisation of a peace sign on the side of the Kienberg, the artificial hill made out of construction debris in the center of the park. This is one of the highest spot in Berlin and allows a view a surprisingly green glance at the city from East.

Moving north along the Wuhle, small tributary river of the Spree, from the park we move towards the generic housing blocks surrounded by green spaces, silence, with almost no human in sight. Alte Hellersdorfer strasse calls for the original existence of a dorf, a village whose first traces go back to 13th Century, but no signs of previous settlements emerges form the modern landscape.

The names of the streets in this area reference other locations, (East) German villages and towns of ancient origin like Eisenach, Kyritz, Gotha, Ferch , Cottbus (wonderful names, aren’t they?). Obvious the question of what actually connects these places to the local context. Was the people living in these blocks originally coming from such localities? Is it rather an arbitrary choice, connecting the Berlin with a wider “national geography”? And who is actually living here, are they really all Herren Schmidt ? To what extent is the gentrification of central districts of Berlin relocating population towards the periphery? From Kottbusser Tor to Cottbusser straße?

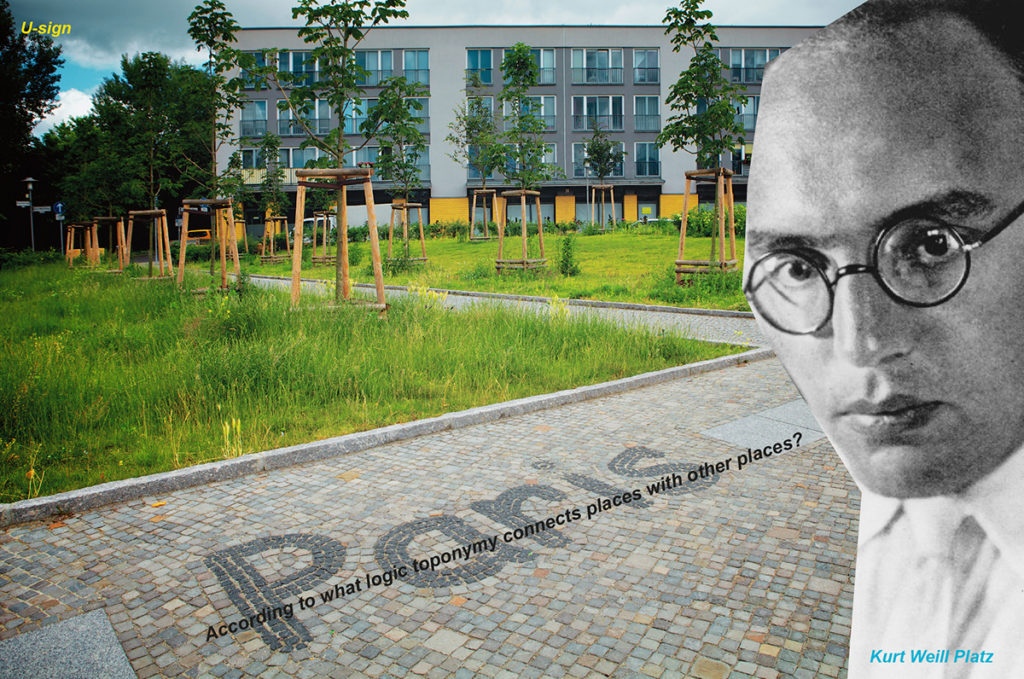

Our trajectory suddendly flows into a more recent settlement, a place that does not conceals its ambition to be a new urban centrality, and this is reflected again into toponyms with reference to an international cultural geography. Kurt Weill Platz is designed according to the personal and professional geography of the important German composer, with different spots dedicated to Paris, London and New York, cities where he lived and was active. From here we get to a square dedicated to Fritz Lang. Coherently a huge Multiplex movie theatre has been realised here, together with commercial arcades and facilities realised on the typical anonymous architectural style of ordinary shopping malls. Far, far from the expressionist design quality that the name would have deserved…

The cultural aspiration of this little suburban Potdsamer Platz is remarked by the toponymy dedicated to such names as Oskar Kokoschka, Peter Weiss, Lily Dagover, Lyonel Feininger. Finally we reach our last station in the Platz dedicated to Alice Salomon, an extraordinary figure of social worker and reformer. Once again, a German forced by her ideas and belief to leave Germany, as many of the historical characters that were chosen to name this new settlement. What we found here is a geography of removal and exile, somehow representing once again the profound identity of this city as a place of transit, of regeneration, a mythological urban creature between chimera and phaenix. For sure, what clearly emerges is the perpetual conflictual dialectics of engraving and erasing memory into the body of the city.